Most people reading this blog will be well aware, because it has been widely reported, that in all UK countries the rates of children looked after are increasing year on year. In England, the number has risen from 50,900 in 1997 to 72,670 in 2017.

However, not all local authorities have seen a rise. To try to make sense of this, we looked at some of the publicly-available data on English local authorities. Taking data available over the last five years, between 2012 and 2017, we looked at three things:

- Which local authorities had higher or lower average rates of children in care (per 10,000 children in the population) and how this varied by region.

- The trends over time in rates of children looked after.

- Factors associated with higher or lower average rates and with increases or decreases in rates over time.

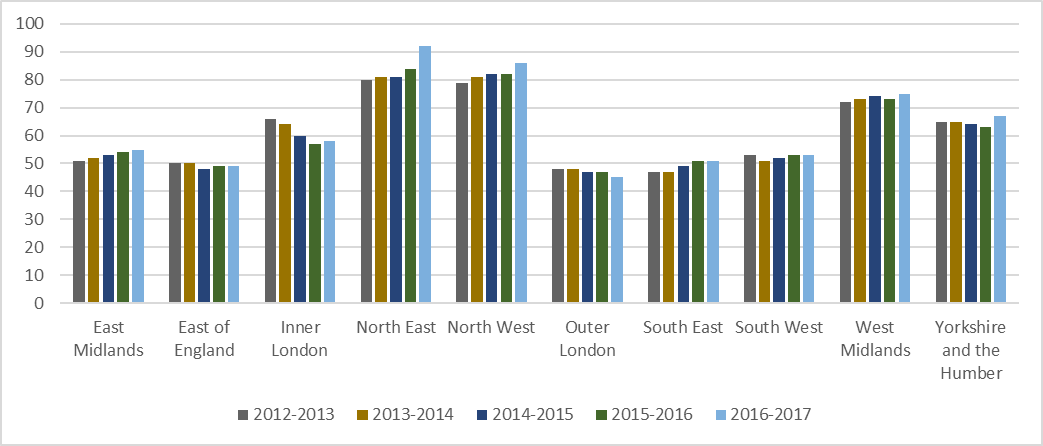

One thing to highlight here is that there were large regional differences. For example, the North of England had the highest rates of children in care, which were rising over time. In London, especially inner London, the rates of children in care were falling over time. We can see this in the graph below.

Average number of looked after children per 10,000 children by region between 2012 and 2017 in England (N=151)

When it comes to changes in care rates over time, 60% of local authorities saw an average rise between 2012 and 2017, 36% saw an average fall and 4% averaged out as having no change at all.

It was very interesting to see which factors predicted rates going down. A decrease in poverty over time was associated with a decrease in care rates. Local authorities who took part in the Innovation Programme were more likely to have decreasing care rates. Local authorities who had higher Ofsted ratings were also more likely to see a decrease in the rate of children looked after.

What do we make of this?

Our interpretation is that both economic factors and service quality matter. The average change in the proportion of lowest income families in a local authority from the start of the recession was the factor most strongly associated with change in care rates. So the socio-economic profile of the local population is certainly a very relevant factor. This is in keeping with the findings of the Child Welfare Inequalities Project. However, as we looked at trends in the rate of children in care over time rather than at one point in time only, this report adds new insights and not simply more of the same.

Ofsted ratings and involvement in the Innovation Programme, which reflect local social work practice, were also associated with decreases in care rates. Therefore, it is not a question of either economic factors OR service quality affecting child protection. Both are important. The economy certainly affects the societal problems that children’s services respond to. It would be wrong to deny that. However, the quality of social work service provision is also important. But it is not the case that social care is completely powerless in the face of economic forces.

Ideally, we would have been able to test whether any of these factors had a more important underlying influence on change in care rates. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to do this kind of test – a multivariate model – because data were not available for all of these factors for the same time period, which meant that we would not have been comparing like with like.

So what’s next?

This was an initial exploratory study to help set the context for other studies looking at what works in reducing the need for out-of-home care. We’ll be following up some of the findings in subsequent studies:

- One of our Change projects is about devolving budgets so that social workers and families decide together how money is spent to try and prevent children coming into care. Reducing family poverty – and also the stress of living in poverty – should feature here.

- We will be reviewing the existing evidence on what works in reducing the need for care, looking at several different intervention themes. These themes include the impact on care rates of changes in family finances, changes in social work practice and changes in therapeutic approaches.

If you would like to read the full report, it is available here: Exploratory analyses of the rates of children looked after in English local authorities (2012-2017)