As outlined in our previous blog, WWCSC and the Early Intervention Foundation have been working on behalf of the Department for Education, with a number of local authorities (LAs) to understand the changes made to practice in response to COVID-19.

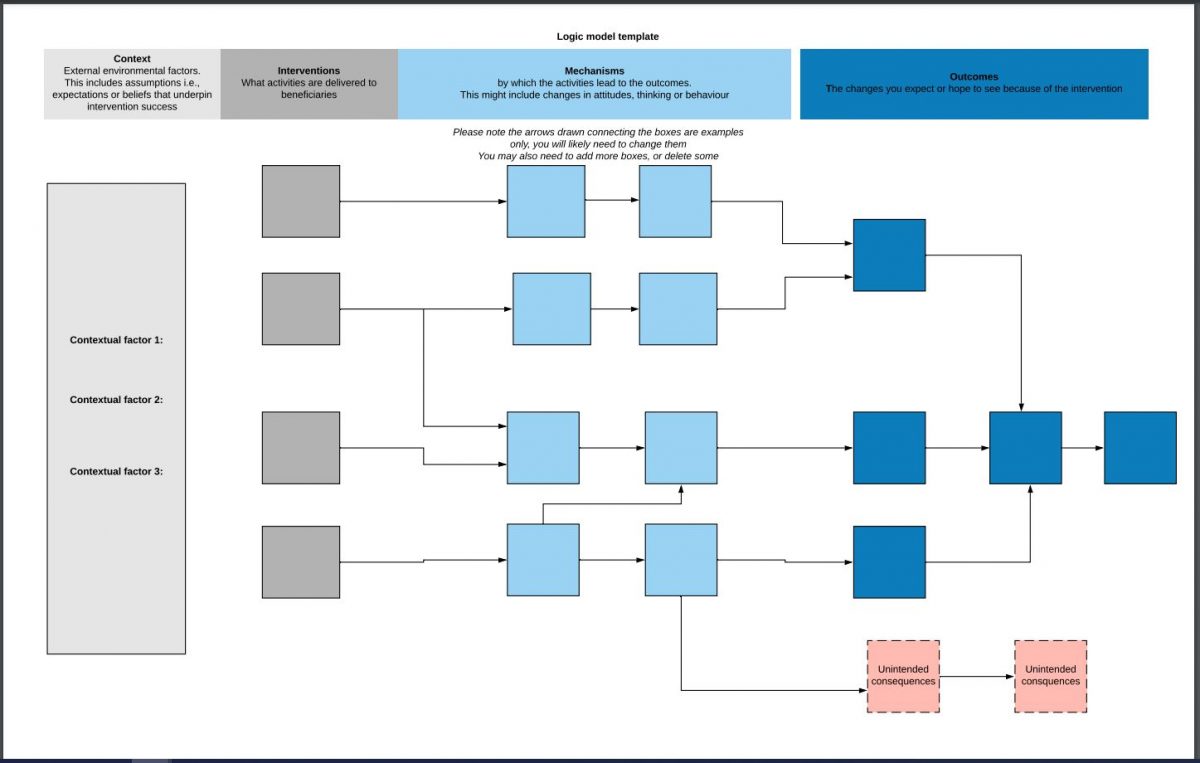

As part of this, we’ve run sessions with each of the participating LAs to develop a logic model for their new models of practice. These outline clearly the key components of what each site has done, the context of the intervention, the mechanisms through which it works and the outcomes they hope to achieve.

The process of creating a logic model is helpful, as it can:

- Outline what an intervention is, the background context, and the component parts, which helps partners to understand what they are doing. This also enables others who may be interested in a similar intervention to understand what is needed if they were to replicate this.

- Ensure that LAs have a clearly defined process for how they think their intervention works, deconstructing the mechanisms through which it achieves their desired outcomes, as well as highlighting any potential negative consequences.

- Guide the development of an evaluation for the intervention, by visualising what the key outcomes are, which can then help understand what measures could be used to generate evidence of impact and ‘what works’.

- Act as a visual overview of the intervention, to provide insight for others, and to demonstrate that the intervention is thoughtful and considered, to support promotion or applications for funding.

It’s been wonderful to see such a high level of engagement, creativity, and hard work from each of the partners involved. They’ve all engaged in the process in different ways. For one site, going through the process of creating the logic model made them realise that a key driver behind the positive changes was the freedom and passion to drive through innovative practice afforded to people implementing the intervention. Another partner used the process to focus on what was needed to move from ‘phase one’ of the innovation, as an immediate response to the pandemic, to a more holistic ‘phase two’ where they were trying to instill broader organisational change with a strong value-base.

The process has shown us how, for many LAs, the immediate changes forced by COVID-19 have led to significant reflection on the role of Children’s Services, engagement with communities, and what we focus on when we think of success. A number of themes have emerged from these conversations: a recalibration of services to focus on community need; multiagency discussions of risk and vulnerability; and the effectiveness of a ‘hybrid’ model of provision, combining the advantages of in-person communication and the efficiency of virtual meetings and support. Collectively, the overarching theme is working flexibly and proactively to respond to individual needs.

As we move onto the final stage of the project, supporting sites to conduct small-scale evaluations of their intervention, these initial conversations led by practitioners will feed into looking at sustaining and developing innovation, a greater evidence base and ultimately improved outcomes for children and families.